Fæder ūre: The Incredible 1,000-Year Journey of the Lord’s Prayer in English

Explore the fascinating evolution of the Lord’s Prayer. We trace its journey from Aramaic, through Old English, to the familiar words we use in Britain today.

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase through these links, we may earn a commission at no additional cost to you.

You probably know the words by heart. Maybe you mumbled them in school assembly, belted them out in church, or heard them spoken at a solemn state occasion. The Lord’s Prayer is woven so deeply into the fabric of British life that it feels like it’s always been there, unchanging and eternal. But the familiar words—”Our Father, who art in heaven”—are just the latest chapter in an epic story of translation, rebellion, and linguistic transformation that spans two millennia and countless languages.

The prayer you know is a ghost. It’s haunted by the echoes of ancient Aramaic, classical Greek, and the formal Latin of the Roman Empire. And, most importantly for us, its DNA was forged in the fiery furnaces of the English language itself, from the guttural poetry of the Anglo-Saxons to the revolutionary pamphlets of the Reformation.

This isn’t just a story about religion. It’s the story of our language. To trace the journey of the Lord’s Prayer is to watch English be born, grow up, and conquer the world. So, let’s pull back the curtain and meet the ancestors of the prayer we think we know so well, starting with its very first utterance.

The Prayer’s Roots: Before English Was English

Before a single word of it was written in English, the Lord’s Prayer had already lived several lives. It began not as a written text but as a spoken teaching, offered by a charismatic Jewish preacher in a forgotten corner of the Roman Empire.

Jesus’s Aramaic Original: The Words No One Wrote Down

Jesus didn’t speak English, Latin, or even the Greek his followers would later use to write about him. He spoke Aramaic, a Semitic language that was the common tongue of Judea in the first century. So, the very first “Our Father” would have sounded something like “Abba d’bashmayya.”

Imagine it: not in the hushed, polite tones of a cathedral, but spoken under a dusty olive tree to a small group of fishermen and tax collectors. Scholars believe the original Aramaic was likely shorter and more poetic than the versions we have now. Aramaic is a language of raw emotion and directness. The word “Abba” is particularly striking. It’s not a formal title like “Father”; it’s a much more intimate word, closer to “Dad” or “Daddy.” Right from the start, this was a prayer that broke the mould, suggesting a deeply personal and loving relationship with God, which was a radical idea for its time.

Because it was an oral teaching, no one wrote it down at the moment it was spoken. What we have are translations of memories, which is where the story gets complicated.

The Greek Accounts: Matthew vs. Luke

The first time the prayer was written down was a generation after Jesus, in the Gospels of the New Testament. And here, we immediately hit a puzzle. There are two different versions.

In the Gospel of Matthew (Chapter 6), the prayer appears as part of the Sermon on the Mount. It’s longer and more structured, presented as a model of how to pray correctly.

In the Gospel of Luke (Chapter 11), it’s shorter. The disciples ask Jesus, “Lord, teach us to pray,” and he offers a more concise version.

Why the difference? Most scholars think Luke’s version is probably closer to the original Aramaic, while Matthew’s version was expanded a little for use in early Christian worship services. It’s Matthew’s version that became the foundation for the prayer we know and love today. It includes phrases like “Your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven” and the famous sign-off, “But deliver us from evil,” which are missing from Luke’s account.

These Greek texts, written in the common Koine Greek of the Roman Empire, were the definitive versions for centuries. For the early Church, this was the prayer.

The Latin Vulgate: How ‘Pater Noster’ Ruled for 1,000 Years

As the Roman Empire grew, Latin became the language of power, law, and, eventually, the Church in the West. Around 400 AD, a brilliant but famously grumpy scholar named St. Jerome was tasked with creating a definitive Latin Bible. His translation, known as the Vulgate (meaning “common”), became the official scripture of the Catholic Church for over a thousand years.

Jerome translated the Greek prayer into the “Pater Noster.”

Pater noster, qui es in caelis, sanctificetur nomen tuum. Adveniat regnum tuum. Fiat voluntas tua, sicut in caelo et in terra.

For centuries, if you were a Christian in Europe—from a peasant in Somerset to a king in France—this was the only Lord’s Prayer you would ever hear. It was chanted by monks, whispered by knights, and recited by scholars. The problem? Almost nobody understood what it meant. Latin was the language of the educated elite. For the common person, the words were a holy mystery, a string of sounds they were told had great power.

This disconnect—between the prayer of the people and the language of the people—would eventually set the stage for a revolution. And that revolution would happen here, in Britain.

Fæder ūre: The Prayer Arrives in England

Long before the Norman Conquest, before Chaucer wrote his tales, and before there was even a king of all England, the Anglo-Saxons were wrestling the Lord’s Prayer into their own tongue: Old English.

The First English Scribbles

Christianity came to Anglo-Saxon England in waves, first with the Romans and later with missionaries from Ireland and Rome in the 6th and 7th centuries. As monasteries were established in places like Lindisfarne and Canterbury, monks began the slow, painstaking work of translation.

At first, they didn’t dare translate the prayer itself. That would have been seen as disrespectful to the holy Latin. Instead, they wrote tiny Old English words directly above the Latin ones in their manuscripts. This is called a “gloss.” It was a cheat sheet for monks who weren’t fluent in Latin.

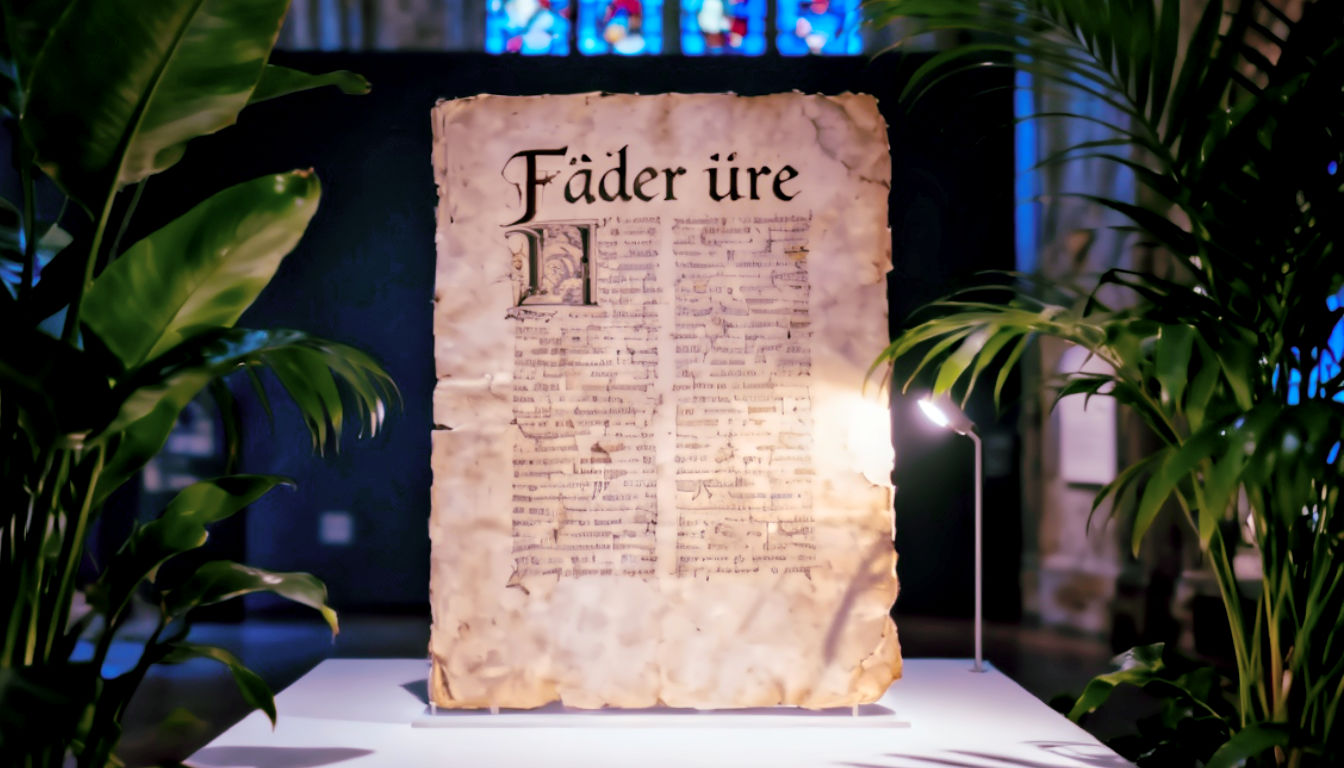

But eventually, full translations began to appear. By the 10th century, we find the Lord’s Prayer written entirely in Old English. It’s a version that is at once alien and eerily familiar. This is the “Fæder ūre”:

Fæder ūre, þū þe eart on heofonum, sī þīn nama gehālgod. Tōbecume þīn rīce. Ġewurðe þīn willa on eorðan swā swā on heofonum.

Let’s break that down:

- “Fæder ūre” is clearly “Father our.”

- “þū þe eart on heofonum” means “thou that art in heaven.” The letter þ (called a thorn) made a “th” sound.

- “sī þīn nama gehālgod” is “be thy name hallowed.” Our word “hallowed” comes directly from the Old English gehālgod.

- “Tōbecume þīn rīce” translates to “come thy kingdom.” The word rīce (pronounced ‘ree-che’) meant kingdom or realm—it’s the same root as the German “Reich.”

Reading it feels like looking at a distant ancestor. You can see the family resemblance, but the features are strange and archaic. This was the Lord’s Prayer of the people who fought the Vikings and told the epic poem Beowulf. It was the language of King Alfred the Great.

Viking Invasions and Linguistic Shifts

The constant raids and eventual settlement of the Vikings (the Danes) in the north and east of England had a huge impact on the English language. Old Norse words crashed into Old English, simplifying grammar and adding new vocabulary. This linguistic melting pot began to slowly cook the language, preparing it for its next great transformation. The Old English of the Fæder ūre was living on borrowed time.

From ‘Oure Fadir’ to ‘Our Father’: A Middle English Revolution

In 1066, everything changed. The Norman Conquest didn’t just give England a new king; it gave the language a new boss. For the next 300 years, the official language of the court, of law, and of power was Norman French. English became the language of the common folk, looked down upon as vulgar and unrefined.

The language of the Church, however, remained Latin. So, for the average person, religion was now conducted in two languages they didn’t speak. But underground, English was bubbling away, absorbing thousands of French words and changing its grammar. The result was Middle English, the language of Geoffrey Chaucer. It’s a version of English we can read today with a bit of effort.

John Wycliffe and the First English Bible

By the late 14th century, there was a growing hunger for a Bible in the language of the people. The Church was powerful and, in the eyes of many, corrupt. An Oxford scholar named John Wycliffe became the figurehead of a reform movement. He believed that ordinary people had the right to read the word of God for themselves.

This was a dangerous, radical idea. To translate the Bible from the sacred Latin into common English was seen as heresy. The Church authorities were horrified. But Wycliffe and his followers did it anyway, producing the first complete English Bible around 1380. And in it was a new version of the Lord’s Prayer:

Oure Fadir þat art in heuenes, halwid be þi name. þi reume come to. Be þi wille don in erþe as in heuene.

You can see the shift immediately. The strange Anglo-Saxon letters are gone. The grammar is simpler and more direct. “Kingdom” has become reume (from the French royaume), though it would later be replaced. This was a Lord’s Prayer for the age of plague, peasant revolts, and the first stirrings of a new English identity.

Wycliffe’s Bible was banned, and his followers were persecuted. But he had lit a fuse. The idea that every person in Britain should be able to understand their own prayers could not be un-thought.

The Prayer We Know Today: The Tudor Reformation

The 16th century was a time of religious upheaval across Europe. In England, Henry VIII’s desire for a divorce triggered the Reformation, which tore the country away from the Catholic Church and created the Church of England. This moment of political and religious chaos created the perfect environment for another, more successful, attempt to put the Bible into English.

William Tyndale’s Groundbreaking Translation

Enter William Tyndale, a brilliant scholar and linguist who was obsessed with the idea of an English Bible. Unlike Wycliffe, who worked from the Latin Vulgate, Tyndale went back to the original Greek and Hebrew scriptures. He believed the Latin version had become corrupted over time and wanted to get back to the source.

Because translating the Bible was still illegal in England, Tyndale fled to Germany. Working in secret, he produced a translation of the New Testament in 1526 that was so powerful, so clear, and so beautifully written that it became the bedrock of the English Bible for the next 400 years. It’s estimated that over 80% of the King James Bible is pure Tyndale.

His Lord’s Prayer is astonishingly modern. It’s the moment the prayer clicks into a form we instantly recognise:

O oure father which arte in heven, halowed be thy name. Let thy kyngdome come. Thy wyll be fulfilled, as well in erth, as it ys in heven.

The spelling is a bit wonky to our eyes, but the words and the rhythm are there. This is our prayer. Tyndale’s genius was his commitment to simple, everyday English. He wanted the “boy that driveth the plough” to know more of the scripture than the Pope. His language is muscular, direct, and full of life.

For his troubles, Tyndale was hunted down, betrayed, strangled, and burned at the stake in 1536. His last words were reportedly, “Lord! Open the King of England’s eyes.”

The Great Bible and The Book of Common Prayer

Ironically, just a few years after his death, Tyndale’s wish came true. Henry VIII, wanting to cement his position as head of the Church of England, authorised the creation of an official English Bible—the Great Bible of 1539. The translators leaned heavily on Tyndale’s forbidden work.

But the final, definitive version of the Lord’s Prayer for the Anglican tradition was cemented by Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Cranmer was the chief architect of the Book of Common Prayer (first published in 1549, revised in 1552 and again in 1662). This book was a masterpiece of English prose. It set out the entire liturgy of the Church of England—all the services, all the prayers, all the psalms—in one volume, in English.

Cranmer took Tyndale’s prayer and polished it, giving it the majestic, lyrical quality we know today.

Here is the version from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, which remains the official prayer book of the Church of England:

Our Father, which art in heaven, Hallowed be thy Name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done, in earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our trespasses, As we forgive them that trespass against us. And lead us not into temptation; But deliver us from evil. Amen.

This is it. The final form. It’s almost identical to Tyndale’s, but Cranmer’s subtle tweaks gave it a rhythm that made it perfect for being spoken aloud by a congregation. It has remained largely unchanged for nearly 500 years, a testament to the combined genius of Tyndale and Cranmer.

‘Debts’ or ‘Trespasses’? The Great Debate

There’s one word in the prayer that has caused more debate than any other: trespasses. If you’ve ever travelled to Scotland or America, you might have heard people say “forgive us our debts” instead. So where did these two different versions come from?

The answer lies back in those original Greek manuscripts.

- The Gospel of Matthew uses the Greek word opheilēmata, which literally means “debts.” In the Aramaic culture Jesus lived in, “debt” was a common metaphor for sin.

- The Gospel of Luke uses the Greek word hamartias, which is the more general word for “sins.”

When St. Jerome translated the Bible into Latin, he used debita (debts) in his version of Matthew. Wycliffe, translating from the Latin, also used “dettis.”

So why did we end up with “trespasses”? This was William Tyndale’s unique choice. When translating Matthew, he decided that “debts” would sound strange to English ears. People would think of financial debts, not moral failings. He looked for a word that better captured the idea of crossing a boundary or doing wrong to someone. He chose “trespasses.”

It was a brilliant move. “Trespass” was a word everyone understood. It meant to unlawfully enter someone’s land or to wrong them. When Thomas Cranmer compiled the Book of Common Prayer, he stuck with Tyndale’s “trespasses,” cementing it in the Anglican tradition.

Most other English translations, including the one that would become the King James Bible, went back to the literal translation of “debts.” This is why there’s a split. The Church of England and its offshoots (the Anglican Communion) say “trespasses” because of the Book of Common Prayer. Many other Protestant denominations, particularly in Scotland (Presbyterians) and the USA, say “debts,” following the King James Bible tradition more closely.

The Enduring Power of the Prayer in Britain

The Lord’s Prayer isn’t a museum piece. It’s a living part of British culture, echoing through our history and institutions.

- In Our Institutions: For centuries, it has been recited daily in the House of Commons at the start of proceedings. It was a mandatory part of the day in almost every school in the country until quite recently. It is an immovable fixture at state occasions, from coronations to Remembrance Sunday services at the Cenotaph.

- In Our Culture: It has been set to music by dozens of British composers, from the Tudor master Thomas Tallis to the modern church music of John Rutter. It appears in the works of our greatest writers, from Shakespeare to Dickens, often used at moments of great crisis or reflection.

- In Our Language: Phrases from the prayer have seeped into our everyday language. We talk about “our daily bread” when referring to our livelihood, or we might plead “lead us not into temptation” with a wry smile when faced with a slice of cake.

A Timeless Prayer in a Changing Tongue

The journey of the Lord’s Prayer is the story of our nation in miniature. It began as a foreign import, spoken in a dead language only the priests understood. It was then seized, fought over, and painstakingly translated into the tongue of the common person by rebels and scholars who risked their lives to do so. It was polished and perfected until it became a jewel of English prose, a prayer that has given comfort and meaning to millions of Britons for half a millennium.

From the Anglo-Saxon Fæder ūre to the Tudor Our Father, every word is a fossil, a clue that tells us who we were and how our language came to be. The next time you hear or say those familiar words, listen closely. You might just hear the echoes of history whispering back.

Further Reading

For those interested in exploring this topic further, these resources provide excellent, authoritative information:

- The British Library: Explore digitised images of William Tyndale’s original 1526 New Testament.

- The Church of England: The official text of the Lord’s Prayer from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.

- The History of English Podcast by Kevin Stroud: An incredibly detailed and accessible podcast that traces the development of the English language, often referencing the translation of religious texts.

- “The Story of English in 100 Words” by David Crystal: A fascinating book by one of the world’s leading language experts, which includes entries on words crucial to the prayer’s history.